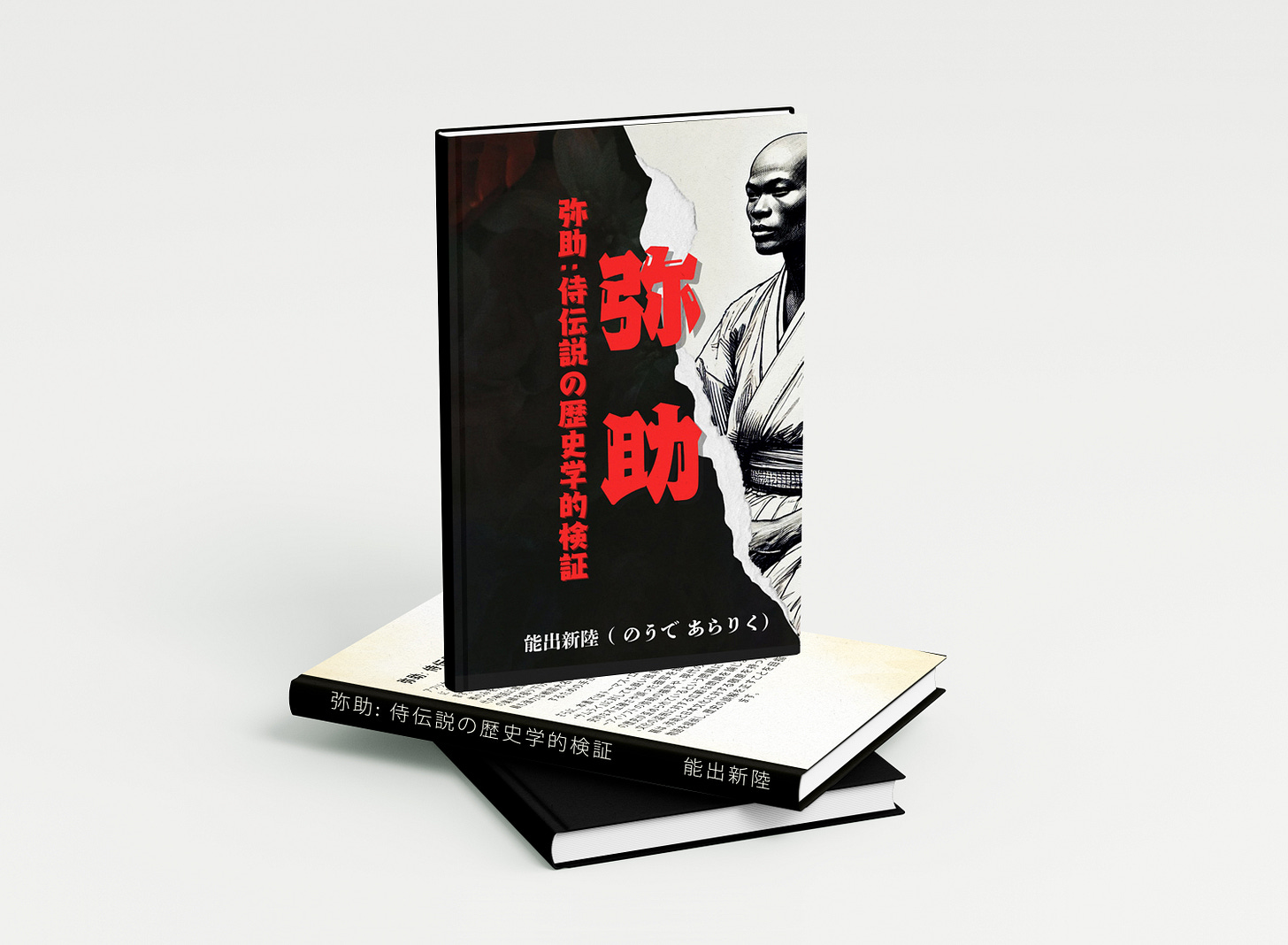

Yasuke : Debunking Pseudo-historical Myths about Black Samurai

Yasuke is an interesting historical figure but a samurai he was not.

In the landscape of world history, the narratives of individuals from diverse backgrounds have often been obscured or romanticized to fit contemporary ideologies. The story of Yasuke, a man of African origin who found his way to Japan during the tumultuous Sengoku period, serves as a compelling case study of this phenomenon. Yasuke's historical journey from possibly being a slave to becoming a retainer in the household of Oda Nobunaga, one of Japan's most influential daimyō, is a narrative ripe for exploration and reinterpretation.

This narrative, however, has not been immune to the influences of Afrocentric romanticism, particularly strong among followers of the Afrocentric ideology in North America. This ideological perspective often seeks to rewrite history to an Afrocentric ideal, leading to romanticized and sometimes ahistorical myths that elevate Yasuke from his documented role as a koshō (小姓, a page or sword-bearer) to that of a samurai. This embellishment stems from a deeper cultural and historical yearning among descendants of slaves in North America, who, severed from their ancestral roots, often seek to reclaim or co-opt histories that offer a sense of pride and belonging. Yasuke's story, in this context, is transformed into a symbol of black empowerment and achievement, despite the limited historical documentation supporting such a grandiose role.

Yasuke arrived in Japan in 1579, in the service of the Italian Jesuit missionary Alessandro Valignano. His tenure in Japan, though brief—lasting from 17 August 1579 to 21 June 1582—marked him as one of the earliest recorded Africans in Japanese history. Unlike the narratives propelled by Afrocentric romanticism, historical documents portray Yasuke not as a samurai but as a retainer to Oda Nobunaga. He was given a stipend, indicating his status was not that of a slave.

The accounts of Yasuke's life in Japan are sparse and originate from fragmentary sources such as the letters of the Jesuit missionary Luís Fróis, the Shinchō Kōki (信長公記, Nobunaga Official Chronicle), and other contemporaneous records. These documents offer glimpses into his life and the fascination his presence sparked in the Japanese court, yet they fall short of supporting the notion of Yasuke as a samurai. His origins, before meeting Nobunaga, are shrouded in mystery, with some sources suggesting he came from Portuguese East Africa (modern-day Mozambique) or India, potentially as a servant or a slave who gained his freedom before arriving in Japan.

What are Samurai?

The samurai of feudal Japan occupied a pivotal role in the social and military hierarchy, embodying the martial ethos of a society governed by the code of Bushido, which emphasized honor, discipline, and loyalty. This elite warrior class did not merely comprise common soldiers but was deeply entrenched in the societal structure, necessitating noble lineage or the favor of a powerful lord for an individual to be inducted into its ranks. The elevation to samurai status was, therefore, not just a recognition of martial prowess but a comprehensive incorporation into a rigid social stratum that dictated one's role, responsibilities, and privileges.

The Samurai Hierarchy

The samurai hierarchy was intricately linked with the feudal system of Japan, where land and the people who worked it were under the control of a lord or daimyō. At the top of this hierarchy was the Shogun, the military dictator, followed by the daimyō, who were powerful regional lords. The samurai served directly under these lords as their military retainers, receiving land or stipends in exchange for their martial services. The distinction between a samurai and a common foot soldier (ashigaru) was stark, with the former enjoying a significantly higher social status, which was often hereditary. The samurai were expected to be adept in various martial arts, especially swordsmanship, and were bound by a strict ethical code.

This requirement of noble blood or lordly favor for samurai status underscores a fundamental aspect of feudal Japanese society: the permeability between different social strata was minimal. Despite the romanticized narratives surrounding figures like Yasuke, the historical prerequisites for becoming a samurai were rigid and typically unattainable for foreigners or commoners without extremely exceptional circumstances such as being adopted by a samurai family or having exceptional martial skills and personal qualities.

Comparison with the Western Knight System

The samurai can be likened to the knights of medieval Europe in several ways. Both were part of a broader feudal system that relied on land tenure and service in a military capacity. Knights, like samurai, often came from noble families, and their status was hereditary. They were bound by chivalry, a code of conduct that, like Bushido, emphasized honor, bravery, and loyalty to one's lord.

However, there are notable differences between the two. The path to knighthood in the West was structured around the concept of training and serving as a page and squire before being knighted, a process that emphasized individual achievement and service. In contrast, while personal achievement and martial prowess were highly valued among samurai, the hereditary aspect of their status was more pronounced, often predetermining their place in the social hierarchy from birth.

Another key difference lies in the role of religion and ideology. The code of chivalry was deeply intertwined with Christian values, and knights often fought in religious wars, such as the Crusades. The samurai, on the other hand, were influenced by a blend of Shinto, Buddhism, and Confucianism, which shaped their ethical code and worldview.

In terms of Yasuke's narrative, the comparison sheds light on the significant barriers he would have faced in achieving the status of a samurai, given the stringent requirements of noble lineage and the deeply ingrained social stratification of feudal Japan. While his role as a retainer to Oda Nobunaga placed him in a respected position within Nobunaga's household, equating this with the formal status of a samurai overlooks the complex interplay of social, cultural, and military factors that defined samurai identity.

The Koshō Conundrum

In highlighting the roles and responsibilities of a koshō in feudal Japan, it's crucial to underscore that, despite their training, loyalty, and proximity to power, koshō were distinctly separate from the samurai class. These pages or attendants, often young men or boys serving samurai, daimyō, and other high-ranking figures, occupied a unique position within the Japanese feudal hierarchy that did not grant them the status, privileges, or recognition of a samurai.

The distinction between koshō and samurai is rooted deeply in the social and military structure of feudal Japan. The samurai class was not just a military designation but a social caste that required noble lineage or significant personal achievement recognized by a lord. Being a samurai entailed not only martial prowess but also adherence to Bushido, the way of the warrior, which encompassed a strict ethical code, lifestyle, and philosophy. Entry into this class was tightly controlled and could not be attained merely through service or loyalty.

In contrast, the role of a koshō, while embodying aspects of loyalty and martial skill, was primarily that of a servant and personal attendant. Their duties, though sometimes involving protection of their master, did not elevate them to the status of a samurai. They did not inherit or acquire the social standing, rights to bear a full range of arms, or the ceremonial honors associated with the samurai class. Moreover, the expectation for a koshō to potentially act as a human shield in times of danger underscores their role as protectors, but this protective duty was a function of their servitude rather than an indication of samurai status.

This clear demarcation between the roles and statuses of koshō and samurai highlights the rigid social stratification of feudal Japan. While a koshō might earn respect and trust within their master's household, this did not equate to an elevation to the samurai class. Their lives and duties, steeped in loyalty and service, were integral to the functioning of the feudal lordships and the personal lives of the samurai they served. However, their position remained fundamentally that of a servant, distinct from the elevated social, military, and ethical standing of the samurai.

Yasuke's unique position within Oda Nobunaga's retinue indeed suggests a certain level of privilege not commonly afforded to every attendant or servant. One of the most telling signs of this privilege was his permission to carry a short sword, or wakizashi, to protect his master. In feudal Japan, the right to bear arms was closely regulated and symbolized a measure of authority and status. While full samurai were typically allowed to carry both a long sword (katana) and a short sword (wakizashi) as part of their daishō, for a non-samurai like Yasuke, being allowed even a short sword was significant.

Yasuke's presence in Nobunaga's retinue, and the privileges he was afforded, such as bearing a sword, likely made him an object of considerable interest and perhaps even a "show off" item. In a society where black individuals were virtually unknown and often only heard of in stories or legends, Yasuke's physical appearance and his prominent role within such a powerful daimyō's household would have attracted attention and curiosity. Nobunaga's decision to keep Yasuke close and to grant him certain privileges might have been influenced not so much by any special capabilities or loyalty on Yasuke’s part but rather the novelty and prestige associated with having such a unique figure at his side.

The historical record on Yasuke's life in Japan ends somewhat abruptly and with little detail regarding his departure from Japan or the later years of his life. Following the tragic Honnō-ji Incident in 1582, where Oda Nobunaga was betrayed and forced to commit seppuku (ritual suicide) by one of his own generals, Akechi Mitsuhide, the fate of Yasuke took a turn. After Nobunaga's death, Yasuke is reported to have fought alongside Nobunaga's forces and was eventually captured by Mitsuhide's soldiers.

The accounts suggest that instead of being killed, Yasuke was taken to the Jesuit missionaries in Kyoto. Mitsuhide reportedly deemed Yasuke as a non-threat, referring to him as a "beast" and not worthy of the same treatment as a Japanese warrior (thereby killing a person of lowly rank after capture could lead Mitsuhide to lose face). This perception spared Yasuke's life but also underscored the foreigner's precarious position in Japan, outside the social and military structures that defined Japanese society at the time.

Following this, historical traces of Yasuke disappear. There are no detailed records of his leaving Japan or of his life afterward. It's possible that Yasuke remained with the Jesuits, who may have facilitated his departure from Japan, perhaps returning to India or even Africa. However, any such movements are speculative, given the lack of concrete evidence.

Yasuke's departure from Japan, shrouded in mystery and lacking in documentation, leaves much to the imagination. His presence in Japan, noted for its uniqueness and the remarkable circumstances under which he served one of the most powerful daimyōs of the period, fades into the realm of speculation and folklore beyond 1582. The lack of records might also reflect the turbulent period that followed Nobunaga's death, with power struggles and the eventual unification of Japan under Tokugawa Ieyasu overshadowing individual stories like Yasuke's.

This is the most thoroughly researched explanation of the recent developments involving Japan and Ubisoft. It's appalling to see an attempt to turn fanfiction into fact and to propagate a fabricated narrative in the West. The Japanese have every right to be upset about the disregard for their significant historical figures in favor of emphasizing a foreigner who was just one of the thousands Nobunaga collected as a curiosity. Japanese historians have even produced records of an event where Nobunaga hired over 100 sumo wrestlers for entertainment. After the event, he granted each of them a title, land, a stipend, and a ceremonial wakizashi. These historians also reviewed records of Nobunaga's court hierarchy, which revealed that all of the sumo wrestlers ranked above Yasuke, suggesting that he was likely named as an entertainer and held a position of minimal importance, likely due to his foreign status.

Wow... No offense but you are totally wrong.

- NHK has defended their broadcast from 2021 on July 24th, and stated no issue with their broadcast calling Yasuke a Samurai (Based on Japanese Law - Broadcasting Act). AKA Japan's public broadcasting which is the second largest source of News stand by the fact Yasuke IS a samurai.

- More people in Japan are aware of Yasuke as a Samurai in Japan (33%) than of the Assassin's Creed/Yasuke issue (29%) based on a survey of 3,700+ which is more than 3x larger than your average election poll.

- There is no academically peer reviewed published work that claims he is not. The most recent paper on him in June of this year says he is...

- The reason why Japanese people are upset is due to two fake rumors being spread that 1) Lockley stated that Japan started slavery which is not true and has been debunked 2) On the Japanese net there was talk of rumors in the US that there were 100s of Black Samurai that shaped Japanese history including famous samurais people know by name. This rumor only exists as a rumor as no substantial discussion exists on the English social media sphere.

I could go on and on...